A simplified homotopy perturbation method

for nonlinear ill-posed operator equations

in Hilbert spaces

Abstract.

One popular regularization technique for handling both linear and nonlinear ill-posed problems is Homotopy perturbation. In order to solve nonlinear ill-posed problems, we investigate an iteratively-regularized simplified version of the Homotopy perturbation approach in this study. We examine the method’s thorough convergence analysis under typical circumstances, focusing on the nonlinearity and the convergence rate under a Hölder-type source condition. Lastly, numerical simulations are run to confirm the method’s effectiveness.

Key words and phrases:

Nonlinear ill-posed operator equations, Iterative regularization methods, Nonlinear operators on Hilbert spaces, Convergence analysis, Homotopy perturbation method2005 Mathematics Subject Classification:

65J15, 65J22, 65F22, 47J061. Introduction

There are numerous scientific and engineering applications that can lead to inverse problems. When inverse issues are formulated mathematically, they typically result in ill-posedness in the sense of Hadamard. Therefore, to find a stable approximation solution for the inverse issue, the regularization method is necessary. Numerous regularization techniques, including the Gauss-Newton iterative approach, the Thikhonov method, the Levrentiv iterative method, and the Levenberg Marquardt method, have been developed in the literature to address issues of this nature in Hilbert spaces (see, for example, [2], [3], [6], [10], [12], [16], [17], and [18]). One of the most popular iterative techniques for resolving nonlinear ill-posed problems in Hilbert spaces is the Landweber technique (cf. [4], [8], [11], [21], and [22]). Compared to other regularization techniques, this one is simpler to implement. A detailed explanation of this technique for the linear case can be found in [5].

In order to comprehend this approach, let us look at the abstract operator equation

| (1) |

In this equation, is a nonlinear operator on , and and are Hilbert spaces with inner product and norm respectively. These operators can always be recognized by their context. represents the Fréchet derivative of at . Assume for the moment that is the exact solution (which does not need to be unique) to (1.1). We are mainly interested in problems of the form (1) for which the solution does not depend continuously on the data . In real-world applications, precise data might not be accessible. Therefore, instead of using the actual data , we use the available perturbed data with

| (2) |

where is the noise level.

Given that is locally scaled and Fréchet differentiable, let

| (3) |

where is the initial guess for the exact solution and . Next, Hanke et al. [8] examined the standard Landweber iteration for the non-linear case, which is as follows:

| (4) |

where indicates the adjoint of the Fréchet derivative for , and is the initial guess for the exact solution. To examine technique (4), they took into account the following tangential type nonlinearity condition: With and ,

| (5) |

The method’s convergence analysis was conducted with the condition (5). For , the iteration is terminated at by the generalised discrepancy principle

| (6) |

where is the positive constant dependent on . Under the subsequent Hölder-type source condition, they were able to determine the rate of convergence:

| (7) |

To determine the rate of convergence for the approach (4), they also needed the following features of , as the assumption (7) is insufficient:

| (8) |

where is the family of bounded linear operators such that

| (9) |

where C is a positive constant.

Li Cao, Bo Han, and Wei Wang initially created homotopy perturbation iteration for nonlinear ill-posed problems in Hilbert spaces (cf. [14], [15]). The main idea behind it is to integrate the homotopy methodology with the standard perturbation method, and incorporate an embedding homotopy parameter. With as the notation The formula for the N-order homotopy perturbation iteration technique

| (10) |

Notably, (10) can alternatively be understood as the steps conventional Landweber iteration for resolving the linearized issue [9] as follows: . It is possible to obtain the classical Landweber iteration (4) by using the one-order approximation truncation (N = 1). The homotopy perturbation iteration in [14] can be produced using the two-order approximation truncation (N = 2):

| (11) |

It is demonstrated that, in comparison to (4), just half-time is required for (11). It was then successfully used for the inversion of the well log restricted seismic waveform [7]. The convergence study in [15] was conducted with respect to the stopping rule (6) and the nonlinearity condition (5). Additionally, they calculated the convergence rate based on assumption (7), (8) and (9).

It should be emphasised that each repetition step of the procedures in (4) and (11) necessitates the computation of the Fréchet derivative. Under the source condition (7), which is dependent upon the unknown answer , the rate of convergence for each of the aforementioned approaches has been determined. Numerous scholars have explored various versions of the simplified iterative approach and have solved this issue (cf. [11], [16], [17], [18], [19] and [20]). The computation cost of the technique decreases dramatically when compared to the simplified version of the method, which just computes the Fréchet derivative at the first guess for the exact solution .

Driven by this benefit, we present a simplified version of the Homotopy perturbation iteration (11), denoted as

| (12) |

where and indicate adjoint of the operator . While the approach (11) includes the derivative at each iterate step , our method just uses the Fréchet derivative at the first guess . Thus, our approach simplifies the assumptions made in [14] and [15] while simultaneously reducing the computational cost. In this paper, we will examine the convergence analysis of the method (12), using the Morozov type discrepancy principle and appropriate assumptions on the nonlinear operator . The method’s rate of convergence under the Hölder-type source condition will also be examined. Finally, we will provide a numerical example to validate our approach.

2. Convergence Analysis of the Method

To prove the method’s convergence, we utilise the following assumptions on the nonlinear operator .

Assumption 1.

(i) For every , where is the solution to (1), there exists .

(ii) The nonlinear operator is scaled appropriately, i.e.,

| (13) |

holds.

(iii) The local property

| (14) |

is satisfied by the operator in a ball , where and .

A number of publications utilise assumptions similar to 1 (iii) for the convergence analysis of ill-posed equations (cf. [8], [12], [16], [17], [19], [20], [22]). Assumption 1 (iii) can be understood as the tangential cone condition on the operator .

From equation (14), the triangle inequality yields the following immediately: for every

| (15) |

We obtain the inequality from (13)

| (16) |

When dealing with noisy data, the iterations are unable to converge but can nevertheless yield a stable approximation of , as long as they are terminated using the Morozov-type stopping criterion after steps, i.e.,

| (17) |

where is a positive constant depending on .

The monotonicity of the iteration error is shown by the following theorem.

Theorem 1.

Proof.

The right-hand side is negative due to (2.5) by the stated condition, , , and . We have confirmed (18) and demonstrated the monotonically declining nature of the iteration error. In fact, we have confirmed that the inequality

is true for every if .

Consequently, using induction, we obtain

The proof is now complete. ∎

Remark 2.

In the event that , we can demonstrate that

| (20) |

Thus, a well-defined stopping index is determined using the discrepancy principle (17) with .

Proof.

Let be any solution of (1) in , and put

| (21) |

is monotonically decreasing to some according to Theorem 1. Next, we demonstrate that is a Cauchy sequence. In the case of , we select such that and

| (22) |

Firstly, we have

| (23) |

and

| (24) |

The final two terms of (2) on both right sides converge to zero for . Now, we use equations (12) and (15) to demonstrate how, as approaches , also reduces to zero:

Likewise, it may be demonstrated that

Our subsequent findings indicate that the Landweber iteration becomes a regularization technique as a result of this stopping rule.

Theorem 4.

The proof has a resemblance to [8, Theorem 2.4].

3. Convergence rates

We calculate the suggested iteration’s rate of convergence in this section. The rate of convergence for the iteration (11) for the source conditions (7) was found in [15]. We observe that, from a practical standpoint, it is quite challenging to validate such assumptions [23]. We use the following source condition to find the convergent rate of the method:

| (25) |

where is small enough.

These approximations will be applied in this section to get the method’s convergence rate outcome.

Lemma 5 (cf. [12]).

Let be a bounded linear operator with the property and let . Then

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(iii)

Lemma 6 (cf. [12]).

Assume and are positive. Then, independent of , there is a positive constant such that

Theorem 7.

Assume that satisfies (13) and (14), that satisfies (2), and that problem (1) has a solution in . A positive constant relying exclusively on exists if satisfies (25) with and is small enough. This can be demonstrated by

| (26) |

| (27) |

for . As previously, is the stopping index of the discrepancy principle (17) in this case, where . For all , (26) and (27) hold in the case of exact data .

Proof.

The iteration (12) is well-defined according to Theorem 1 since iterates , where , always remain in . Furthermore, when , the stopping index is finite. Substitute . Given , we get the representation from (12)

where and .

This produces the closed expression for the error for

| (28) |

and consequently

We employ induction to demonstrate the result for . The proof is simple for , and we take it for granted that the result holds for any such that , where .

For ,

| (29) | ||||

| (30) | ||||

| (31) | ||||

| (32) | ||||

| (33) |

and

| (34) | ||||

Using the triangle inequality, equations (15), (17) and the induction assumption, we now obtain

| (35) |

and

| (36) | |||||

Consequently,

and

Thus, applying Lemma 6, we obtain

| (37) |

and

| (38) |

where the constants and are dependent on . Therefore

Likewise, one may demonstrate that

| (39) |

Here, and depends on .

Owing to (17), , as follows:

Therefore, using the above result (3), we obtain

This would provide

| (40) |

Therefore,

| (41) |

and

| (42) |

where

∎

Theorem 8.

Assuming the conditions of Theorem 7, we obtain

| (43) |

and

| (44) |

where and are positive constant that depends exclusively on .

Proof.

We have

and

Since we are aware that must be small, we take . Thus, we have

Therefore,

Applying the inequality of interpolation, we obtain

where is positive constant. For ,

| (45) |

and when , we apply (40) with to obtain

| (46) |

where , and hence

where .

Using the outcome that we obtain,

where . ∎

Remark 9.

In contrast to the suggested simplified HPI (12), the HPI (11) taken into consideration in [15] necessitates the extra condition (8) and (9) on the non-linear operator in order to show the convergence rate conclusion. The convergence rate result cannot be maintained in practical problems if the operator does not meet condition (8) and (9). Here, we give an example that does not meet assumptions (8) and (9).

4. Numerical Example

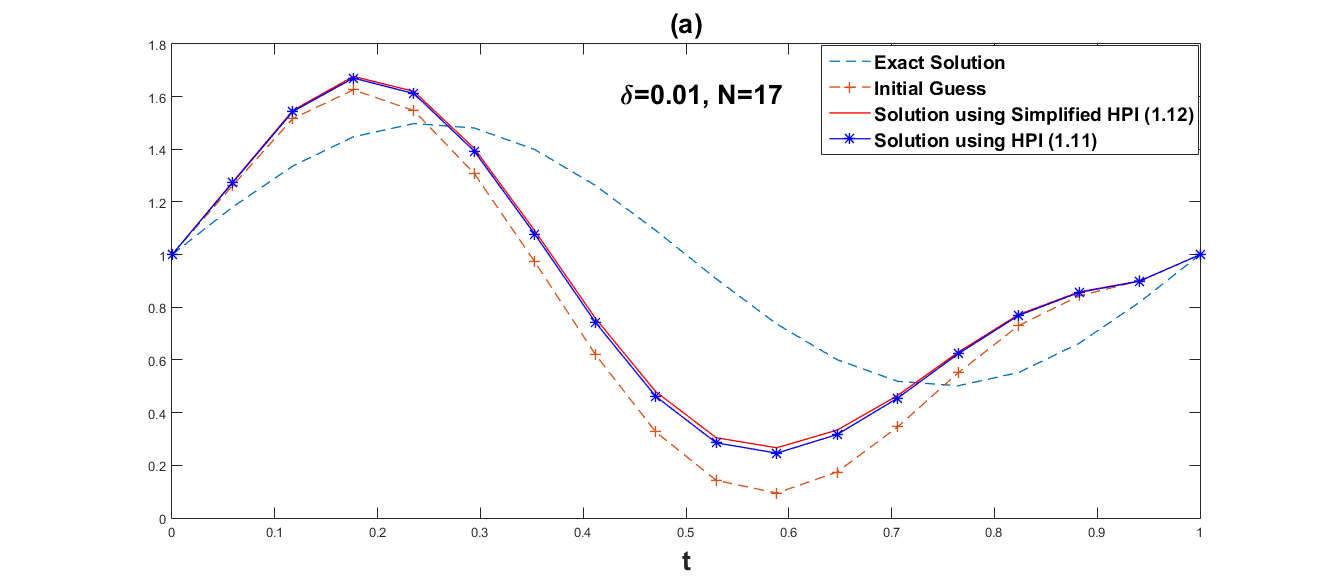

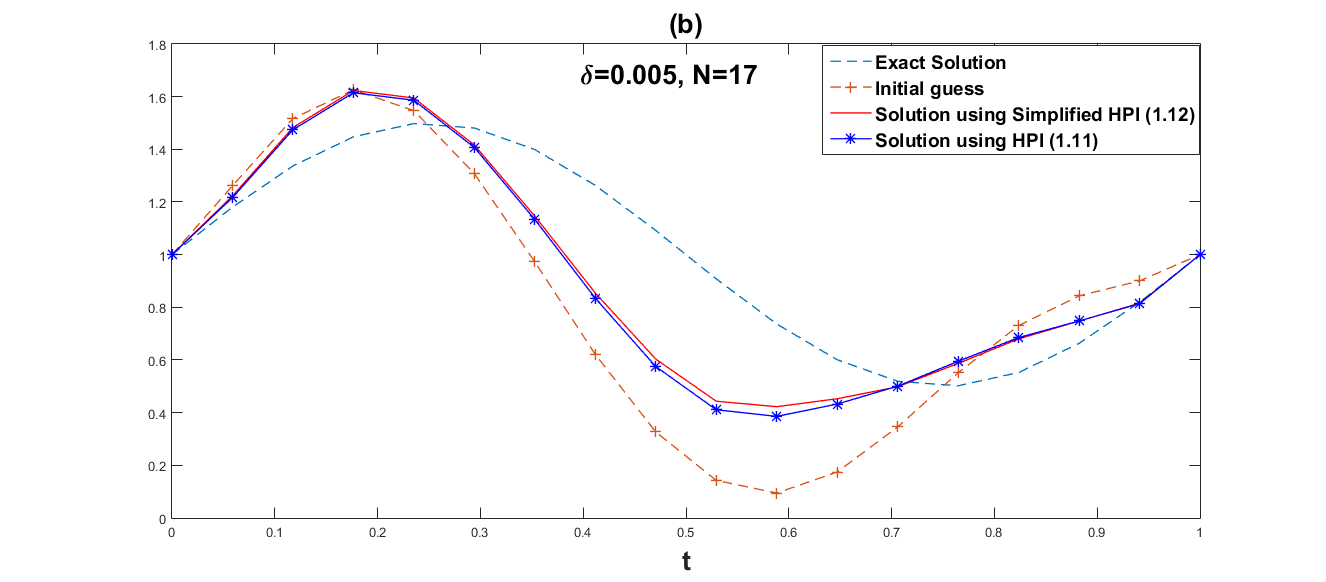

This section examines a numerical example to demonstrate the adaptability of the suggested simplified homotopy method. Matlab is used for numerical calculations.

Here, we look at the nonlinear model problem, which is recovering the parameter estimation problem’s diffusion term. Let and represent an open bounded domain with a Lipschitz border . We examine calculating the diffusion coefficient in equation

| (47) |

We consider that contains the exact diffusion coefficient . In the domain , there is a solution in for every in the domain. We may define the nonlinear operator with by using the Sobolev embedding . It was demonstrated in [6], [8] and [21] that this operator is Fréchet differentiable with

| (48) | ||||

where is defined by and is defined as ; note that is the adjoint of the embedding operator from .

For every in , if , , then (5) holds locally according to Lemma 2.6 in [24], which guarantees the convergence of the HPI (11). Assumption (14) is a particular instance of (5), which guarantees the convergence of the proposed iteration (12) according to the Theorem 3 and Theorem 4.

Convergence rate results do not hold for the HPI (11) since F, regrettably, does not satisfy assumption (8) and (9) (see [11], [24]). We do not need the assumption (8) for the convergence rate results in the suggested simplified HPI (12).

From the iteration (12), for all , . Therefore, in particular , which means . Hence

| (49) |

Assume that . The right-hand side of differential equation (47) is explicitly determined using exact information . By introducing random noise to the precise data at a specified noise level , the perturbed data satisfying is obtained. On a uniform grid with different grid points (N), the differential equations involving the Fréchet differentiable (48) are solved using the finite element method using linear splines. With , the iteration is terminated using the stopping criteria (17).

We use the function

and the exact data , so the exact solution is .

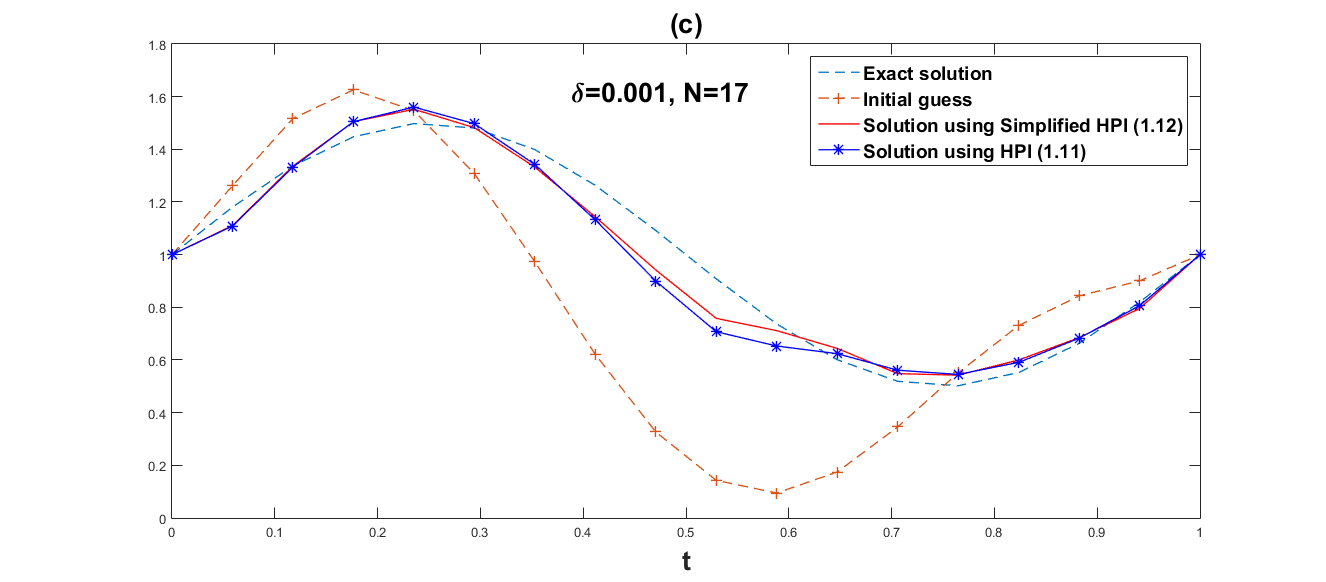

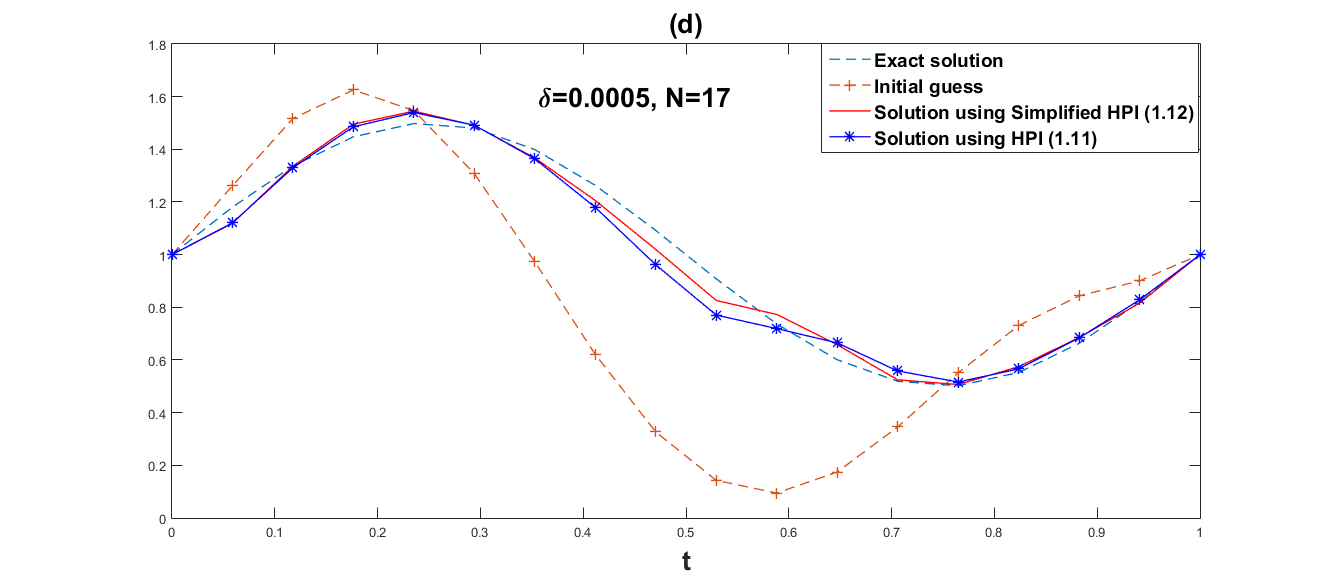

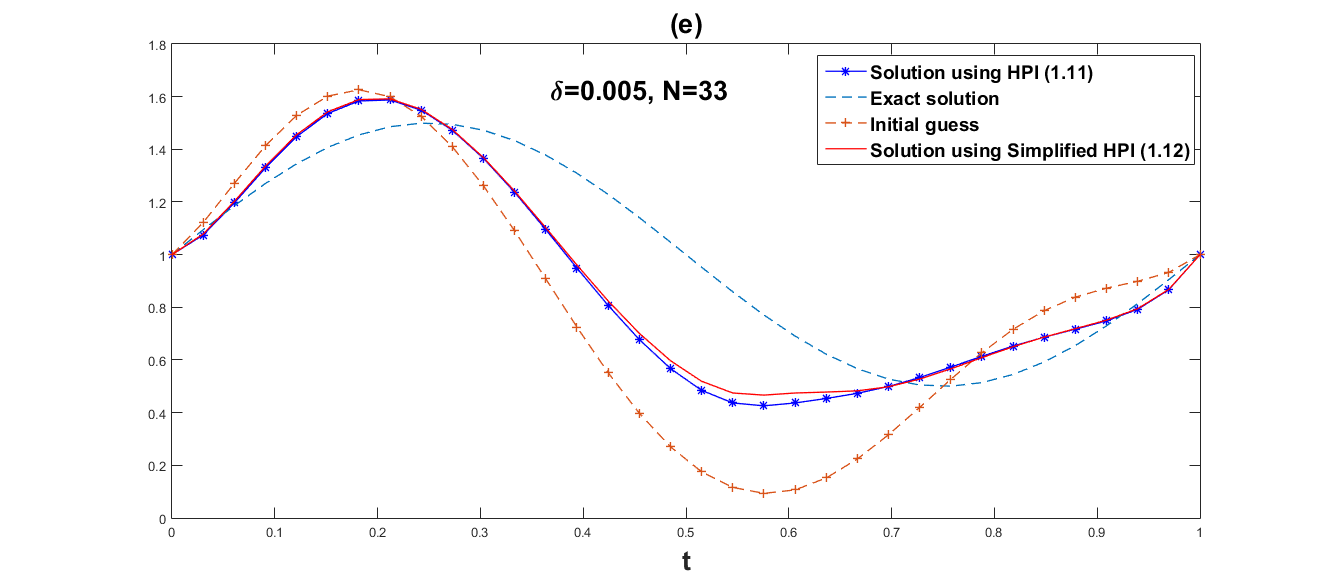

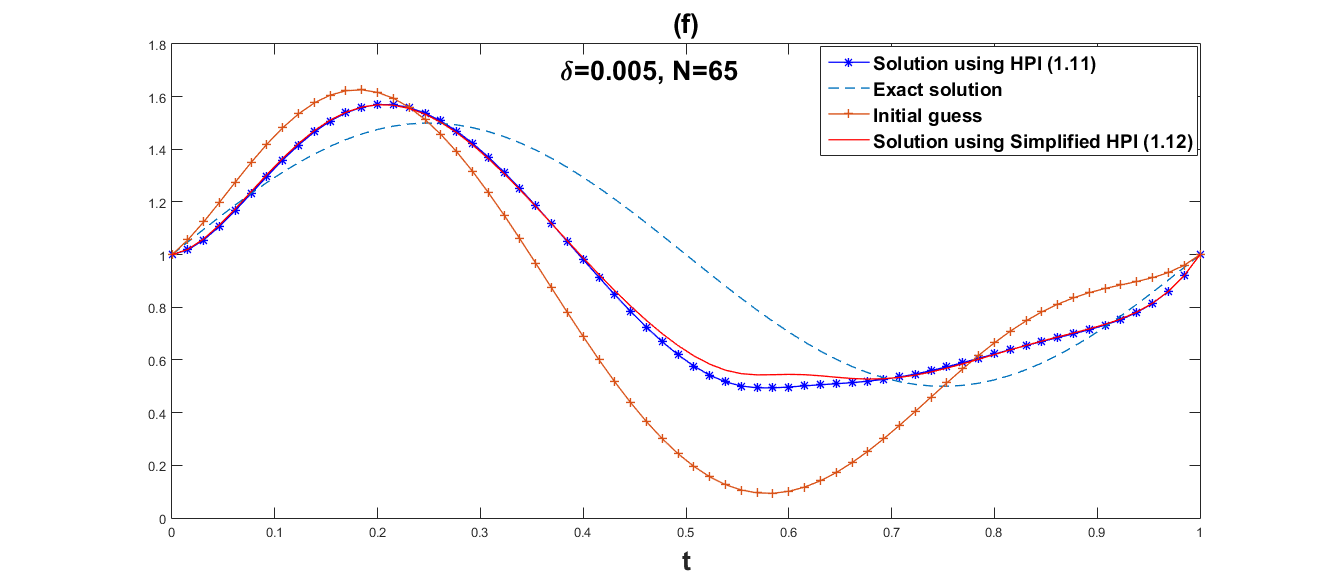

We employ both the suggested simplified Homotopy perturbation iteration (12) and the Homotopy perturbation iteration (11). Several values of and grid point are chosen in order to show how the convergence rates depend on the noise level. The numerical results are given in Table 1 and Table 2. Fig. 1–Fig. 6 respectively, represent graphical results for the methods (11) and (12).

Obviously, Fig. 1–Fig. 6 show that the approximate effect of simplified Homotopy perturbation iteration is better. Compared with Homotopy perturbation iteration, we discover in Table 1 and Table 2 that the error norm of simplified Homotopy perturbation iteration is much smaller within less iteration steps and less computational time, and also the convergent rate of simplified Homotopy perturbation iteration (12) is faster than Homotopy perturbation iteration (11).

| N | Time(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 17 | 424 | 1.3377 | 1.5375 |

| 0.005 | 17 | 4853 | 0.9980 | 16.9290 |

| 0.001 | 17 | 53252 | 0.2844 | 189.9022 |

| 0.0005 | 17 | 134204 | 0.1877 | 421.6156 |

| 0.01 | 33 | 1972 | 1.6762 | 8.7951 |

| 0.005 | 33 | 8511 | 1.1900 | 31.0274 |

| 0.01 | 65 | 4457 | 2.0520 | 21.7195 |

| 0.005 | 65 | 13948 | 1.3607 | 75.8592 |

| N | Time(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 17 | 510 | 1.3569 | 1.8747 |

| 0.005 | 17 | 5970 | 1.0488 | 18.4612 |

| 0.001 | 17 | 83441 | 0.3475 | 265.8005 |

| 0.0005 | 17 | 189874 | 0.2529 | 628.5853 |

| 0.01 | 33 | 2350 | 1.7366 | 9.1521 |

| 0.005 | 33 | 10628 | 1.2667 | 42.0180 |

| 0.01 | 65 | 5312 | 2.1569 | 26.6291 |

| 0.005 | 65 | 18020 | 1.4721 | 91.1350 |

5. Conclusion

In this study, we have performed the analysis and evaluated a simplified version of the Homotopy perturbation iteration (11). The suggested technique has the advantage of just computing the Fréchet derivative once, rather than at each iteration step. The calculation in this approach becomes simpler than the traditional Homotopy perturbation iterations, as the iteration (12) and the source condition (25) only entail the Fréchet derivative at initial guess to the exact solution of (1). The suggested iteration is competitive in terms of reducing the overall computing time as well as error when compared to the traditional Homotopy perturbation iteration as demonstrated by the numerical example.

References

- [1]

- [2] A. B. Bakushinskii, The problem of the iteratively regularized Gauss–Newton method, Comput. Math. Math. Phys., 32 (1992), pp. 1353–1359.

- [3] A. B. Bakushinskii, Iterative methods for solving non-linear operator equations without condition of regularity, Soviet. Math. Dokl., 330 (1993), pp. 282–284.

-

[4]

A. Binder, M. Hanke and O. Scherzer, On the Landweber iteration for nonlinear ill-posed problems, J. Inverse Ill-Posed Probl., 4 (1996), no. 5, pp. 381–389.

https://doi.org/10.1515/jiip.1996.4.5.381

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

- [5] H. W. Engl, M. Hanke and A. Neubauer, Regularization of Inverse problems, Math. Appl., 375, Kluwer Academic publishers group, Dordrecht, 1996.

- [6] H. W. Engl, K. Kunisch and A. Neubauer, Convergence rates for Tikhonov regularization of nonlinear ill-posed problems, Inverse Problems, 5 (1989), no. 4, pp. 523–540.

- [7] H. S. Fu, L. Cao, B. Han, A homotopy perturbation method for well log constrained seismic waveform inversion. Chin. J. Geophys.-Chinese Edition, 55 (2012), no. 9, pp. 3173–3179.

-

[8]

M. Hanke, A. Neubauer and O. Scherzer, A convergence analysis of the Landweber iteration for nonlinear ill-posed problems, Numer. Math., 72 (1995), no. 1, pp. 21–37.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s002110050158

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

- [9] Q. Jin Q, A general convergence analysis of some Newton-Type methods for nonlinear inverse problems. SIAM J. Numer. Anal., 49 (2011), no. 49, pp. 549–573.

-

[10]

Q. Jin, On a regularized Levenberg–Marquardt method for solving nonlinear inverse problems, Numer. Math., 115 (2010), no. 2, pp. 229–259.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00211-009-0275-x

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[11]

J. Jose and M. P. Rajan, A Simplified Landweber Iteration for Solving Nonlinear Ill-Posed Problems, Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math., 3 (2017), no. 1, pp. 1001–1018.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40819-017-0395-4

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

- [12] B. Kaltenbacher, A. Neubauer and O. Scherzer, Iterative Regularization Methods for Nonlinear Ill-Posed Problems, De Gruyter, New York (2008).

-

[13]

B. Kaltenbacher,Regularization by projection with a posteriori discretization level choice for linear and nonlinear ill-posed problems, Inverse Problems, 16 (2000), pp. 1523–1539.

https://doi.org/10.1088/0266-5611/16/5/322

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

- [14] L. Cao, B. Han, W. Wang, Homotopy perturbation method for nonlinear ill-posed operator equations, J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul., 10 (2009), no. 10, pp. 1319–1322.

-

[15]

L. Cao, B. Han, Convergence analysis of the Homotopy perturbation method for solving nonlinear ill-posed operator equations, Comput. Math. Appl., 61 (2011), no. 8, pp. 2058–2061.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.camwa.2010.08.069

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[16]

P. Mahale, M. Nair, A simplified generalized Gauss-Newton method for nonlinear ill-posed problems, Math. Comp., 78 (2009), no. 265, pp. 171–184.

https://doi.org/10.1090/S0025-5718-08-02149-2

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[17]

P. Mahale, Simplified iterated Lavrentiev regularization for nonlinear ill-posed monotone operator equations, Comput. Methods Appl. Math., 17 (2017), no. 2, pp. 269–285.

https://doi.org/10.1515/cmam-2016-0044

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

- [18] P. Mahale and P. K. Dadsena, Simplified Generalized Gauss–Newton Method for Nonlinear Ill-Posed Operator Equations in Hilbert Scales, Comput. Methods Appl. Math., 18 (2018), no. 4, pp. 687–702.

- [19] P. Mahale and K. D. Sharad, Error estimate for simplified iteratively regularized Gauss-Newton method in Banach spaces under Morozove Type stopping rule, J. Inverse Ill-Posed Probl., 20 (2017), no. 2, pp. 321–341.

-

[20]

P. Mahale and K. D. Sharad, Convergence analysis of simplified iteratively regularized Gauss-Newton method in Banach spaces setting, Appl. Anal., 97 (2018), no. 15, pp. 2686–2719.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00036811.2017.1386785

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[21]

A. Neubauer, On Landweber iteration for nonlinear ill-posed problems in Hilbert scales, Numer. Math., 85 (2000), pp. 309–328.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s002110050487

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[22]

O. Scherzer,

A modified Landweber iteration for solving parameter estimation problems, Appl. Math. Optim., 38 (1998), pp. 45–68.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s002459900081

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[23]

O. Scherzer,

Convergence criteria of iterative methods based on Landweber iteration for solving nonlinear problems. J. Math. Anal. Appl., 194 (1995), pp. 911–933.

https://doi.org/10.1006/jmaa.1995.1335

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[24]

O. Scherzer, H. W. Engl and K. Kunisch, Optimal a posteriori parameter choice for Tikhonov regularization for solving nonlinear ill-posed problems, SIAM J. Numer. Anal., 30 (1993), pp. 1796–1838.

https://doi.org/10.1137/0730091

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)